A bit about non-obviousness and theories

It has been said that the reception of any successful new scientific hypothesis goes through three predictable phases before being accepted. First, it is criticized for being untrue. Secondly, after supporting evidence accumulates, it is stated that it may be true, but it is not particularly relevant. Thirdly, after it has clearly influenced the field, it is admitted to be true and relevant, but the same critics assert that the idea was not original

Zihlman, A.L., Pygmy chimps, people, and the pundits. New Scientist 104, 39–40 (1984).

A model of inventiveness for theories

The dismissal-resistance-appropriation pattern called the “stages of truth” has been noted for well over a century (Shallit, 2005). Zihlman’s reference (above) to “the same critics” suggests that the attempt to appropriate a new idea for tradition overlaps with the stage of active resistance. This blog about appropriation uses recent examples to illustrate how pundits normalize or domesticate new results, claiming them for tradition. These examples indicate that the gatekeepers who challenge the validity and importance of a new idea are the same people who attack its originality, e.g., by quote-mining older sources and mashing up new ideas with old ones, to make the new ideas seem more incremental.

This presents a dual challenge to scientists advancing the case for new theories: (1) the challenge of communicating the new idea and making a case for its importance and plausibility, and (2) the struggle to defend against the efforts of gatekeepers to undermine the idea and muddy the waters by blending it with old ideas.

Dismissal, resistance, and appropriation are all evident in reactions to the theory of arrival biases proposed by Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001). Lynch (2007) writes that “The notion that mutation pressure can be a driving force in evolution is not new” (explained here) citing Charles Darwin, Yampolsky and Stoltzfus, and about a half-dozen others, none of whom proposed a recognizable theory of evolution by mutation pressure. The first major commentary on mutation-biased adaptation came out in TREE in 2019: it was a hit-piece that misrepresented the theory and the evidence, and offered multiple attempts at appropriation— the theory is merely part of the neutral theory, it comes from Haldane and Fisher, it is nothing more than contingency, it is the traditional view, etc.[1]

Recently Cano, et al. (2022) showed an effect of mutation-biased adaptation predicted from theory, and one press release framed this effort literally as “helping to return Darwin’s second scenario to its rightful place in evolutionary theory” as if the main idea came from Darwin.

My focus here is not on this process of appropriation or theft that re-assigns credit for our work to others who are more famous, but on the issue of novelty, and how to evaluate it. The kind of novelty that matters in science is untapped potential; assigning credit is a separate issue (think of Mendelian genetics: in 1900, this was a novel idea with huge untapped potential, though an unknown monk had published the idea decades earlier). The theory of arrival biases— proposing a specific population-genetic linkage between tendencies of variation and predictable tendencies of evolution— appeared only in 2001 and is still unknown to most evolutionary biologists. It is not found in textbooks, or in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Evolution, or in the canonical texts of the Modern Synthesis, or in the archives of classical population genetics.

Something is profoundly wrong with suggesting that this theory is not new. Clearly we need a better way to evaluate the novelty of scientific claims than asking whether the claims have thematic content that can be linked back to dead authorities via vague statements.

Here I’m going to use the patent process as a point of reference for evaluating novelty. Patenting an invention and proposing a theory are two different things, but I think the comparison is useful. The law is often where philosophy meets practice: where abstract principles become the basis for adjudicating concrete issues between disputing parties— with life, liberty and treasure at stake. Note that patent law combines credit and novelty: it is about who gets to claim the untapped potential of an invention.

The theory of novelty underlying patent law hinges on non-obviousness. Under US patent law, a successful patent application shows that an invention meets the 4 criteria of eligibility (patentability), newness, usefulness, and non-obviousness. Eligibility is mostly about whether the proposed invention is a manufacturing process, rather than something non-patentable. I will set aside that criterion as irrelevant for our purposes. An invention must have the potential to do something useful.

An invention is new if it is not found in prior art. In patent law, prior art is defined in a very permissive way, to include any prior representation, whether or not the invention was ever manufactured or made public (whereas in science, we might want to restrict the scope of prior art to published knowledge available, for instance, via libraries).

Thus, newness is easy to understand: make one small improvement on prior art, and that is considered new under patent law. But improvement or newness is not enough. In order to be patentable, a new and useful invention must be a non-obvious improvement— non-obvious to a practitioner or knowledgeable expert. In the patent law for some other countries (e.g., Netherlands), the latter two criteria are sometimes combined by saying that the invention must be inventive, meaning both new and non-obvious. An example of an obvious improvement would be to take a welding process widely used with airframes and apply it to bicycle frames.

The most distinctive (i.e., potentially non-obvious) aspects of the theory from Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001) are that (1) it focuses on the introduction process (the transient of an allele frequency as it departs from zero) as a causal process, distinguishing dual causation by origin and fixation (in contrast to the singular conception of population-genetic causes as mass-action forces that shifting frequencies); (2) it links tendencies of evolution to tendencies of variation without requiring neutrality or high mutation rates, in contrast to the mutation-pressure theory of Haldane and Fisher; and (3) it purports to unite disparate phenomena including effects of mutation bias, developmental bias, and the findability of intrinsically likely forms.

The non-obviousness of a pop-gen theory of arrival biases

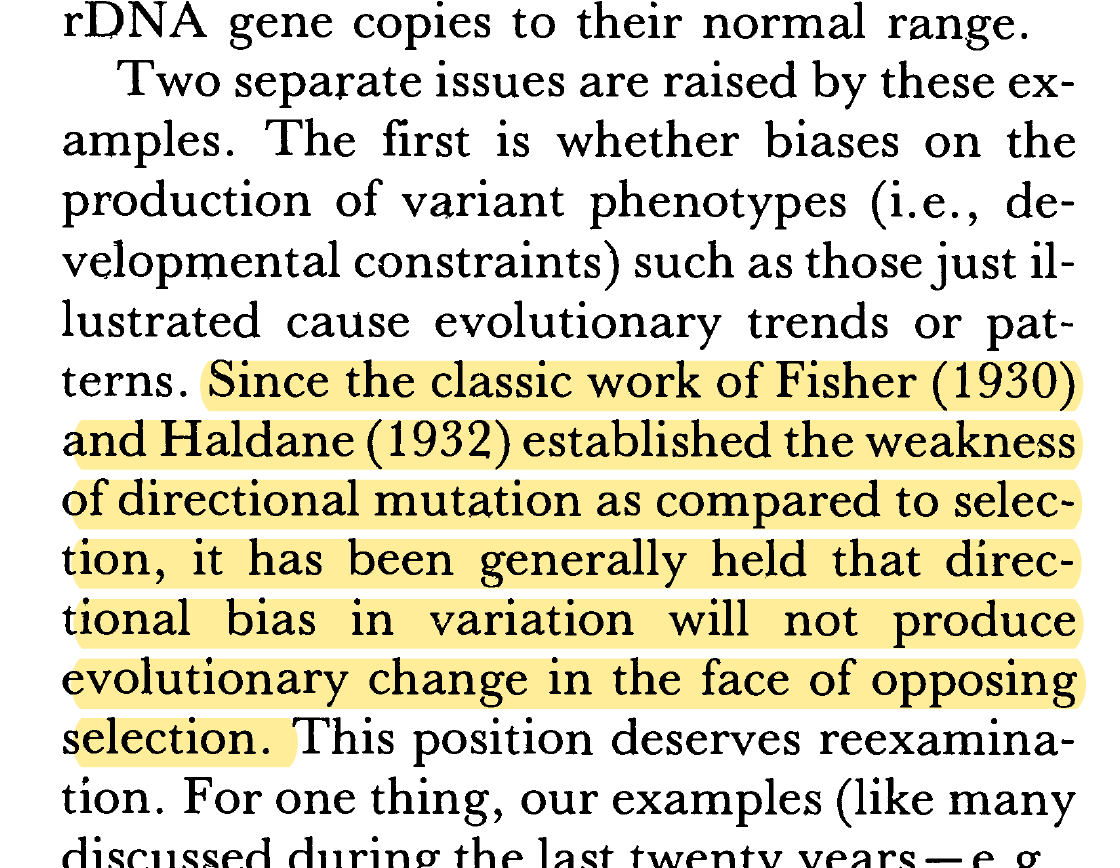

As outlined above, we may consider the theory of arrival biases as a useful and possibly non-obvious improvement on prior art. Prior to 2001, what was the state of the art (in evolutionary thinking) in regard to the potential for internal variational biases to induce directional trends or tendencies in evolution? This general idea was believed to be incompatible with population genetics, based on the opposing pressures argument of Haldane and Fisher, which says that, because mutation rates are small, mutation is a weak pressure, easily overcome by the opposing force of selection.

More broadly, these are the most relevant pieces of prior art from the corpus of population genetics and evolutionary theorizing (to my knowledge, based on years of searching):

- the opposing pressures argument of Haldane (1927, 1932, 1933), Fisher (1930)

- the verbal arguments of King (1971, 1972). See note 3.

- the verbal theory of Vrba and Eldredge (1984). See note 2.

- Mani and Clarke (1990), a theory paper, which shows that mutational order is influential, but treats it as a purely stochastic variable, rather than proposing a theory of biases and generalizing on that

None of these sources actually proposes a population-genetic theory of arrival biases and distinguishes it from evolution by mutation pressure. This means that the theory is new, but it does not, by itself, mean that the theory is non-obvious. An idea could be obvious but no one writes it down because no one cares enough to do so. Indeed, historically, the people with the population-genetics expertise are not the same people as the structuralists searching for internal causes. Population geneticists are obsessed with selection, Fisher, selection, standing variation and selection. We could read stacks of population genetics papers without finding out what anyone thinks about generative biases, which might as well be a reference to voodoo for most population geneticists.

We could solve this problem with a time machine: go back into the 20th century, and get some theoreticians together with internalist-structuralist thinkers to see if they could combine the classic idea of internal variational biases with population genetics. For instance, we could go back to the 1980s and get together some population geneticists with those early evo-devo pioneers (e.g., Pere Alberch) who were literally calling for attention to developmental biases in the introduction of variation. Maybe we could add some philosophers of science.

We do not need a time machine to understand how population geneticists would address structuralist thinking about the role of variation, because this meeting of the minds actually happened, with results recorded in the scientific literature

In fact, we do not need a time machine to understand how population geneticists would address structuralist thinking about the role of variation, because this meeting of the minds actually happened, with results recorded in the scientific literature. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Gould, Alberch and others began to suggest some kind of important evolutionary role for developmental “constraints” that was not included in traditional thinking, as described on the wikipedia page for arrival bias:

Similar thinking [about generative biases acting prior to selection] featured in the emergence of evo-devo, e.g., Alberch (1980) suggests that “in evolution, selection may decide the winner of a given game but development non-randomly defines the players” (p. 665)[23] (see also [24]). Thomson (1985), [25] reviewing multiple volumes addressing the new developmentalist thinking— a book by Raff and Kaufman (1983) [26] and conference volumes edited by Bonner (1982) [27] and Goodwin, et al (1983) [28] — wrote that “The whole thrust of the developmentalist approach to evolution is to explore the possibility that asymmetries in the introduction of variation at the focal level of individual phenotypes, arising from the inherent properties of developing systems, constitutes a powerful source of causation in evolutionary change” (p. 222). Likewise, the paleontologists Elisabeth Vrba and Niles Eldredge summarized this new developmentalist thinking by saying that “bias in the introduction of phenotypic variation may be more important to directional phenotypic evolution than sorting by selection.” [29]

They are literally talking about biases in the introduction of variation. In 1984, a group of scientists and philosophers, all highly regarded, convened at the Mountain Lake biological station to consider how development might shape evolution. In 1985, these 9 eminent scientists and philosopers collaborated to publish “Developmental constraints and evolution”, now considered a landmark paper cited ~1800 times:

- John Maynard Smith, population geneticist trained with Haldane

- Richard Burian, philosopher of science

- Stuart Kauffman, later wrote the Origins of Order

- Pere Alberch, developmental biologist and evo-devo pioneer

- John H Campbell, evolutionary theorist and philosopher of science

- Brian Goodwin, developmental biologist, author of How the Leopard got its Spots

- Russ Lande, developer of the multivariate generalization of QG (trained with Lewontin)

- David Raup, paleontologist

- Lewis Wolpert, developmental biologist

The authors raised the question of what might give developmental biases on the production of variation a legitimate causal status, i.e., the ability to “cause evolutionary trends or patterns.” The only accepted theory of causation was that evolution is caused by the forces of population genetics, i.e., mass-action pressures acting on allele frequencies. Maynard Smith et al. confronted the issue thus, invoking the prior art of Haldane and Fisher:

Although they clearly call for a “reexamination”, they did not provide one, other than a vague suggestion of neutral evolution, which is unsatisfactory because a proposal based on neutrality, though consistent with Haldane-Fisher reasoning, is not a satisfactory foundation for the claims of evo-devo.

Another way of articulating the prior art would be to point to the verbal theories noted above, e.g., the highly developed example of Vrba and Eldredge (1984).[2] Is the population-genetic theory of Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001) an obvious improvement on this verbal theory? Does it merely supply the math that would be obvious from reading Vrba and Eldredge? Again, we can answer this question by reading Maynard Smith, et al (1985), because they are clearly representing the verbal theory from evo-devo that Pere Alberch (one of the authors) promoted. So, if a population-genetic theory of arrival biases was an obvious clarification of this verbal theory, then Pere Alberch could have asked John Maynard Smith and Russ Lande to translate his verbal theory so as to yield a proper population-genetic grounding for his claims. Clearly that did not happen.

I could cite some other examples, but the case could be made entirely on Maynard Smith, et al. (1985). Why does a single paper make such a strong case? First, the author list includes a set of people who are clearly experts on the relevant topics. Second, the authors were clearly focused on the right issue, and were clearly motivated to find a theory to account for the efficacy of biases in variation to influence the course of evolution, arguably the central claim of the paper. Third, this was a seminal paper that got lots of attention and became highly cited (today: 1800 citations). This means that hundreds of other experts must have read and discussed the paper: if this particular set of 9 authors had missed something, others would have pointed it out in response. Instead, years later, critics such as Reeve and Sherman (1993) complained that Maynard Smith, et al. simply re-state the idea of developmental biases in variation, without an evolutionary mechanism linking these biased inputs to biased outputs.

Thus, experts confronted the issue of how biases in variation could act as a population-genetic cause, citing the prior art of Haldane and Fisher. They repeated some of the verbal claims of the developmentalists, but they did not find a causal grounding for these claims in a population-genetic theoory of arrival biases.

QED, a population-genetic theory of arrival biases was non-obvious in 1985.

More non-obviousness with Maynard Smith and Kauffman

To further explore this issue of non-obviousness, let us consider John Maynard Smith’s knowledge of King’s (1971) codon argument, which can be read as an early intuitive appeal to an implication of arrival biases. King argued that the amino acids with more codons would be more common in proteins (as indeed they are) because they offer more options, explaining this with an example implying an effect of variation and not selection. Originally, King and Jukes (1969) proposed this as an implication of the neutral theory, but King (1971) quickly realized that this did not depend on neutrality, but would happen even if all changes were adaptive [3].

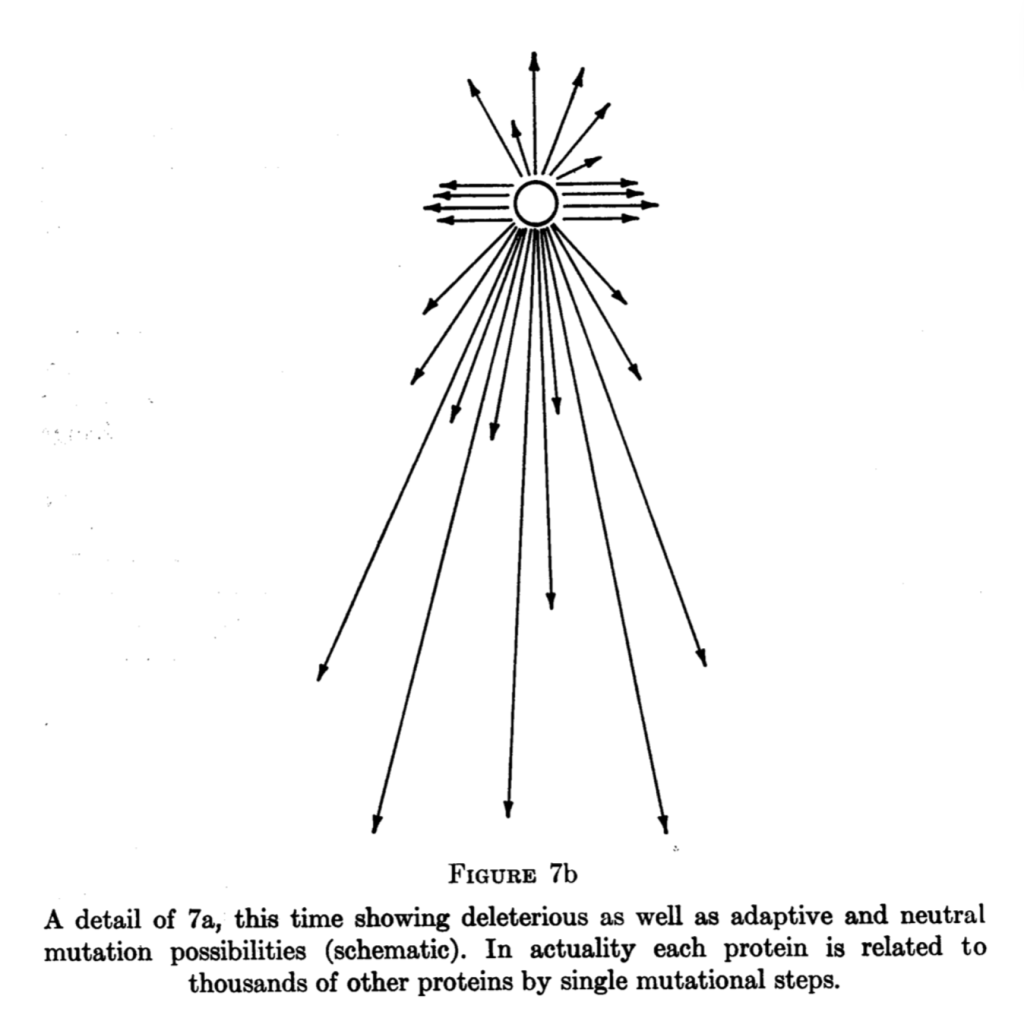

The way we would explain this today is that the genetic code is a genotype-phenotype map that assigns more codon genotypes to certain amino-acid phenotypes. Because these amino acids occupy a greater volume of the sequence-space of genotypic possibilities, they have more mutational arrows pointed at them from other parts of sequence space: this makes them more findable by an evolutionary process that explores sequence space (or genotype space) via mutations. Because of this phenomenon of differential findability reflecting what Ard Louis calls “the arrival of the frequent”, the amino acids with the most codons will tend to be the most common in proteins. This argument does not require neutrality, but merely a process subject to the kinetics of introduction, i.e., it is an argument about kinetic bias. The form of the argument maps to a more general argument about the findability of intrinsically likely phenotypes, which is one of the meanings of Kauffman’s (1993) concept of self-organization.

Maynard Smith literally invented the concept of sequence space (Maynard Smith, 1970). He also knew about King’s codon argument, which he quoted it in his 1975 book, in a passage contrasting the neutralist and selectionist views:

“Hence the correlation does not enable us to decide between the two. However, it is worth remembering that if we accept the selectionist view that most substitutions are selective, we cannot at the same time assume that there is a unique deterministic course for evolution. Instead, we must assume that there are alternative ways in which a protein can evolve, the actual path taken depending on chance events. This seems to be the minimum concession the selectionists will have to make to the neutralists; they may have to concede much more.”

p. 106 of Maynard Smith J. 1975 (same text in 1993 version). The Theory of Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

This just drives home the point about non-obviousness even further. To someone who knows the theory already, King’s argument might look familiar, but Maynard Smith does not recognize a theory connecting generative biases with evolutionary biases that would be useful for understanding evo-devo and solving the challenge of “constraints”. Instead, he refers only to a theory that allows “chance events” to affect the outcome of evolution.[4].

A few years later, Kauffman (1993) published The Origins of Order, offering findability arguments under the heading of “self-organization.” In Kauffman’s reasoning, selection and “self-organization” work together to produce order. But Kauffman never offered a causal theory explaining self-organization in terms of population-genetic processes, so his claims were a bit of a mystery to population geneticists (though his results were never doubted). His simulations typically didn’t include population genetics in the usual sense, but depicted evolutionary change as the series of steps taken by a discrete particle (representing the population) in a discrete space. Thus, the models do not treat introduction and fixation as separate processes.

But there is no longer any mystery: the findability effect emerges from the way that differential representation of phenotypes in genotype-space induces biases in the introduction process, which lead evolution toward the most highly represented forms. This “arrival of the frequent” effect has been demonstrated clearly (in regard to the findability of RNA folds) in work from Ard Louis’s group (see Dingle, et al., 2022). So, we can count Kauffman (1993) as another famous example illustrating non-obviousness, because clearly the theory was non-obvious to Kauffman, and his book was widely read and discussed by evolutionary biologists. If Kauffman had missed a population-genetic basis for self-organization that was obvious to other thinkers, then those other thinkers could have supplied this missing argument. They didn’t, apparently.

This is an important lesson for traditionalists who seem to assume mistakenly that theories are timeless universals (per Platonic realism) and that they are all obvious from assembling the parts. John Maynard Smith had the parts list, in a sense, and he had the chance to glimpse the issue from multiple angles. He got useful clues from the thinking of Jack King. In the circumstances leading up to the famous 1985 paper, Maynard Smith and another brilliant population geneticist (Russ Lande) were placed (figuratively) on an island with developmentalist-structuralist thinkers and they were tasked with making sense of the causal role of developmental biases. In the end, they did not articulate a theory of arrival biases as a potential solution to this problem. Maynard Smith and Lande remained active as theoreticians after 1985 and did not discover the theory.

This should not be taken as a criticism of the abilities of any of these scientists. This is just how reality works, contrary to the assumptions of traditionalist pundits. Maynard Smith himself understood that theories can be elusive. I had the opportunity to meet him several times in the 1990s when he was an external advisor to the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research program in evolutionary biology. He was a great one for sharing stories and talking science with students and post-docs over a beer. He once told a series of humorous anecdotes about scientific theories he almost discovered. In one case, he had run some numbers on the logistic growth equation and found some odd behavior, and then set the problem aside— only to realize much later that he had stumbled on deterministic chaos. The neutral theory was another theory that he almost-but-not-quite discovered. I don’t recall the other examples.

The point here is that scientists, even brilliant ones, can fail to see possibilities that seem obvious in retrospect. When Huxley first read the Origin and learned of Darwin’s theory, he said to himself “How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!”

Confronting attempts at appropriation and minimization

Now, with this background in mind, we can reconsider attempts to appropriate the theory of arrival biases or undermine its novelty. Lynch (2007) and Svensson and Berger (2019) appear to be suggesting that the theory is now new, but is merely part of a tradition going back a century or more.

In science, the way to establish X in prior art is to find a published source and then cite it. Let us consider what this might look like:

“Stoltzfus and Yampolsky (2001) were not the first to propose and demonstrate a population-genetic theory for the efficacy of mutational and developmental biases in the introduction of variation: such a theory was already proposed and demonstrated by Classic Source and subsequently was cited in reviews such as Well Known Review and textbooks such as Popular Textbook”.

But of course, Lynch, Svensson and Berger say nothing like this, because they can’t: no such sources exist. In appropriation arguments, the gap between intention and reality is filled with misleading citations and hand-waving. Returning to the analogy with patents: if this were a dispute over the novelty of a patent claim, every one of the sources cited by Lynch, and every one of the arguments of Svensson and Berger (2019), would be dismissed as irrelevant, because they simply do not establish the existence, in prior art, of a recognizable theory of biases in the introduction of variation as a cause of orientation or direction in evolution.

For instance, Svensson and Berger say that the theory is part of the neutral theory, citing no source for this claim. Kimura wrote an entire book about the neutral theory, along with hundreds of papers. Surely if Svensson and Berger were serious, they could cite a publication from Kimura that expresses the theory. But they have not done this. None of the sources that they cite articulates a theory of arrival biases. Their insinuation that our work-product is not original relative to work cited from Kimura, Haldane, Fisher, or Dobzhansky must be rejected as, not merely false, but a frivolous and damaging misrepresentation that deprives scientists of proper credit for their work (e.g., note how, in their Box 1, Haldane, Fisher and Kimura are named, but Yampolsky and Stoltzfus are not). Lynch’s (2007) bad take (analyzed here) is equally frivolous, but it is merely a fleeting expression of ignorance rather than a concerted attempt to undermine unorthodox claims.

Now, having dismissed attacks on the newness of the theory, let us consider the critique of Svensson and Berger (2019) as an attack on non-obviousness, i.e., they may be insinuating that the theory, though it improves on prior art, fails to satisfy the criterion of being non-obvious, and therefore is not novel, not a genuine invention worthy of recognition. This is one way to read their argument in Box 1, in which they build on work from Haldane, Fisher and Kimura, going from an origin-fixation formalism to a key equation from Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001) that expresses the bias on evolution as a ratio of probabilities Pj / Pj = (uisi) / (uj sj) = (ui / uj) (si / sj), reflecting both biases in introduction and biases in establishment.

The implication is that the theory is obvious because one can put it together from readily available bits. But this just begs the question: does the derivation in Box 1 show that the theory is obvious? If anyone can put the theory together from readily available bits, why didn’t they? Why didn’t Fisher and Haldane do this in the 1930s? Why didn’t Kimura, Lewontin or King in the 1970s? Why didn’t Maynard Smith and Lande in the 1980s?

The attitude of Svensson and Berger (2019) seems to be a case of inception: we planted this theory in their heads, and now they see it everywhere. Yet before we proposed this theory, vastly greater minds than Svensson and Berger had access to the same Modern Synthesis canon and failed to see the theory.

Clearly mathematical cleverness is not the right standard for judging the non-obviousness of scientific theories. An equation is, at best, a model of a theory, useful if you already understand what the theory says. Writing down an equation with the form of a ratio of origin-fixation rates (as in Box 1 of Svensson and Berger) does not magically cause a theory to form in your head. For instance, Lewontin has a structurally similar equation on p. 223 of his 1974 book: it is a ratio of origin-fixation rates for beneficial vs. neutral changes, reducing to 4Ns ub / un. If this equation caused the theory of arrival biases to form in Lewontin’s head, then surely he would have included the theory in the 1979 Spandrels paper, and this would have provided a much more solid grounding for the claims of Gould and Lewontin about the role of non-selective factors in evolution. That didn’t happen (note that, at this time, Lewontin was also familiar with King’s codon argument [5]).

Why was a population-genetic theory of arrival biases so non-obvious? My sense is that the late discovery of this theory reflects a blind spot in evolutionary thinking, the combined effect of habitual approaches to theoretical modeling (e.g., solving for equilibrium behavior), specific notions of causation (e.g., favoring mass action and determinism), the overwhelming influence of neo-Darwinism (selection governs evolution and variation is just a source of random raw materials), and particularly, the threat of ridicule in a neo-Darwinian culture that habitually relies on strawman arguments to link internalist thinking with mysticism and vitalism.

However, understanding why the theory was non-obvious is a separate issue. Whether or not we understand why the theory eluded generations of scientists, it clearly did. The theory may seem obvious today, but it clearly was not obvious in the past, and the empirical proof of this non-obviousness is that Maynard Smith, Lande, Kauffman, Lewontin and many other well qualified evolutionary thinkers had the motive and the opportunity to propose this theory and they did not.

References

King JL, Jukes TH. 1969. Non-Darwinian Evolution. Science 164:788-797.

King JL editor. 1972. Sixth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. 1971 Berkeley, California.

King JL. 1971. The Influence of the Genetic Code on Protein Evolution. In: Schoffeniels E, editor. Biochemical Evolution and the Origin of Life. Viers: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 3-13.

Mani GS, Clarke BC. 1990. Mutational order: a major stochastic process in evolution. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 240:29-37.

Maynard Smith J. 1970. Natural selection and the concept of a protein space. Nature 225:563-564.

Maynard Smith J. 1975. The Theory of Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Maynard Smith J, Burian R, Kauffman S, Alberch P, Campbell J, Goodwin B, Lande R, Raup D, Wolpert L. 1985. Developmental Constraints and Evolution. Quart. Rev. Biol. 60:265-287.

Oster G, Alberch P. 1982. EVOLUTION AND BIFURCATION OF DEVELOPMENTAL PROGRAMS. Evolution 36:444-459.

Reeve HK, Sherman PW. 1993. Adaptation and the Goals of Evolutionary Research. Quarterly Review of Biology 68:1-32.

Shallit J. 2005. Science, Pseudoscience, and The Three Stages of Truth. PDF

Stebbins GL, Lewontin RC. 1971. Comparative evolution at the levels of molecules, organisms and populations. Sixth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. 1971 Berkeley, California.

Vrba ES, Eldredge N. (benchmark; co-authors). 1984. Individuals, hierarchies and processes: towards a more complete evolutionary theory. Paleobiology 10:146-171.

Notes

[1] When I say “hit piece”, I mean that TREE solicited, reviewed and published a highly negative piece without getting feedback from the people whose work was targeted. When we objected to the garbage they published, we were not given space for a rebuttal. This is what institutionalized gatekeeping looks like. We were not given a seat at the table.

[2] The piece by Vrba and Eldredge, 1984 is part of the paleo debate of the 1970s and 1980s. They use very general abstract language, following on early authors such as Oster and Alberch. They refer to biases in the introduction (or production) and sorting (reproductive sorting, to include selection or drift), making a neat dichotomy that they apply at each level of a hierarchy. So, clearly, they see this as a fundamental kind of causation that can be extrapolated to a hierarchy. One strange thing about the argument is the implicit assumption that biases in the introduction of variation are a kind of causation already recognized at the population level, which is not correct. So, the argument is not situated properly. And, because it includes no demonstration, one could not be sure (in 1984) that the theory would actually work. And, because it has no demonstration, and because of the way it refers to prior art, we can’t be sure that references to “introduction” or “production” are references to the population-genetic operator that is coincidentally called “introduction” in the theory of arrival biases. In fact, it seems quite certain that Vrba and Eldgredge could not have had a clear conception of the introduction process, because even the population geneticists of the time did not have a clear conception.

[3] King 1971 presents a verbal argument with a concrete example that is the closest thing I have seen to an earlier statement of the theory of Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001). First, he clearly means for this idea to be general. That is the significance of the diagram with the arrows coming out from a point in a blank space, with some pointing up (beneficial), some laterally (neutral), and many down (deleterious). I have used diagrams like that myself. But he has almost nothing to say on where the biases come from. His motivating example is the genetic code but he does not cite any other example. He does not reference prior art of Haldane and Fisher and does not explain how his theory is different. He does not offer proof of principle other than the verbal model.

[4] I have seen this kind of reaction many times. Saying that chance affects evolution is a familiar thing. Evolutionary biologists are accustomed to a dichotomy of selection (or necessity) and chance, and it is familiar to invoke “chance” as if it were a cause. But it is not familiar in evolutionary biology to refer to generative processes as evolutionary causes that impose biases on the course of evolution. As of today, there is no language for this that is acceptable to traditionalists. So, when traditional thinkers are confronted with the theory of Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001), they often translate this into a familiar selection-vs-chance dichotomy and say that the theory of arrival biases is a theory about how “chance” affects evolution, or they link this to “contingency.” But the theory of arrival biases is not a theory about how chance and contingency affect evolution. It is a theory about how arrival biases affect evolution.

[5] Stebbins and Lewontin (1971) address King’s codon argument in their general rebuttal of neutralist arguments. This paper appears in a symposium volume together with one of King’s papers. So, perhaps all three scientists were present together at this symposium in Berkeley. Stebbins and Lewontin dismiss King’s argument with a reference to “the law of large numbers”.