What on earth is “mutationism”? Some possible answers

The term “mutationism” appeared in the early 20th century in regard to the views of early geneticists such as de Vries, Bateson, Punnett, and Morgan (e.g., Poulton, 1909 or McCabe 1912). These leading thinkers did not use “mutationism” to describe their own diverse views.[1] Perhaps they thought of themselves as free thinkers, not tied to any ideology or “-ism”.

In the contemporary literature, “mutationism” is most often a strawman in which evolution takes place by dramatic mutations alone, without selection (see the conceptual immune system of neo-Darwinism). This pejorative use of “mutationism” continues today in the writings of Synthesis gatekeepers such as Futuyma (2023) or Svensson (2023).

Yet the 2013 book “Mutation-driven Evolution”, by Masatoshi Nei— a pioneer of molecular evolutionary genetics who passed away in early 2023—, brought renewed attention to the idea of a broad alternative to traditional thinking focused on mutation rather than selection. Among published reviews of the book, only Wright rejects Nei’s thinking as mistaken, referring to it as “Mutationism 2.0.” Five other reviews try to explain Nei’s position sympathetically, without necessarily endorsing it. Three reviews do not mention “mutationism” (Brookfield, Galtier, Weiss). The review by Gunter Wagner entitled “The changing face of evolutionary biology”, like my review for Evo & Devo, attempts to identify a sympathetic meaning of “mutationism” appropriate for Nei’s distinctive project, focusing on the importance of mutations in evolution.

One might be tempted to avoid the term “mutationism” (along with “saltationism” and “orthogenesis”) on the grounds of being toxic. To use this term is to risk ridicule and invite misunderstanding. Why do that, when one’s goal is to communicate with readers? I avoided these terms myself for many years, on precisely these grounds. However, eventually I decided not to acquiesce to rhetorical tactics designed to browbeat dissenters using strawman arguments. As we say here in the US, that would be letting the terrorists win. Promoting good intellectual hygiene in our field means calling out fallacies, and addressing alternative views fairly and rigorously, without rhetorical trickery. [2]

If “selectionism” is allowable to designate a focus on selection, without denying a role for mutations in evolution, then “mutationism” is allowable to designate a focus on mutation that does not deny selection.

If there are distinctive features of the views of Nei and the early geneticists, nothing prevents us from using “mutationism” to denote those features. If “selectionism” is allowable to designate a focus on selection, without denying a role for mutations in evolution, then “mutationism” is allowable to designate a focus on mutation that does not deny selection. In my own thinking, I tend to associate “mutationism” with a non-exclusive explanatory position, with the lucky-mutant conception of evolutionary dynamics (see the shift to mutationism is documented in our language), or with a school of thought.

TLDR

| Possible meaning of mutationism | Type of meaning |

| evolution happens by dramatic mutations alone, without selection | Strawman from Synthesis tribal mythology, employed by gatekeepers to police orthodoxy |

| identifying distinctive mutational-developmental changes is a uniquely powerful way to explain the evolution of form | Explanatory position on what kinds of causal attributions are meaningful, key to evo-devo |

| reconstructing mutational changes provides uniquely reliable knowledge of past evolution | Methodological position on which causes are most accessible to scientific methods, also key in evo-devo |

| the timing and character of events of mutation determine the timing and character of evolutionary change | Empirical position on evolutionary dynamics, e.g., in applications of origin-fixation models |

| diverse evolutionary phenomena arise from combining mutation and genetics | Loosely defined school of thought associated with Bateson, Punnett and Morgan |

| a preliminary and imperfect expression of (for instance) a future paradigm of dual causation | Transition state mainly of historical interest |

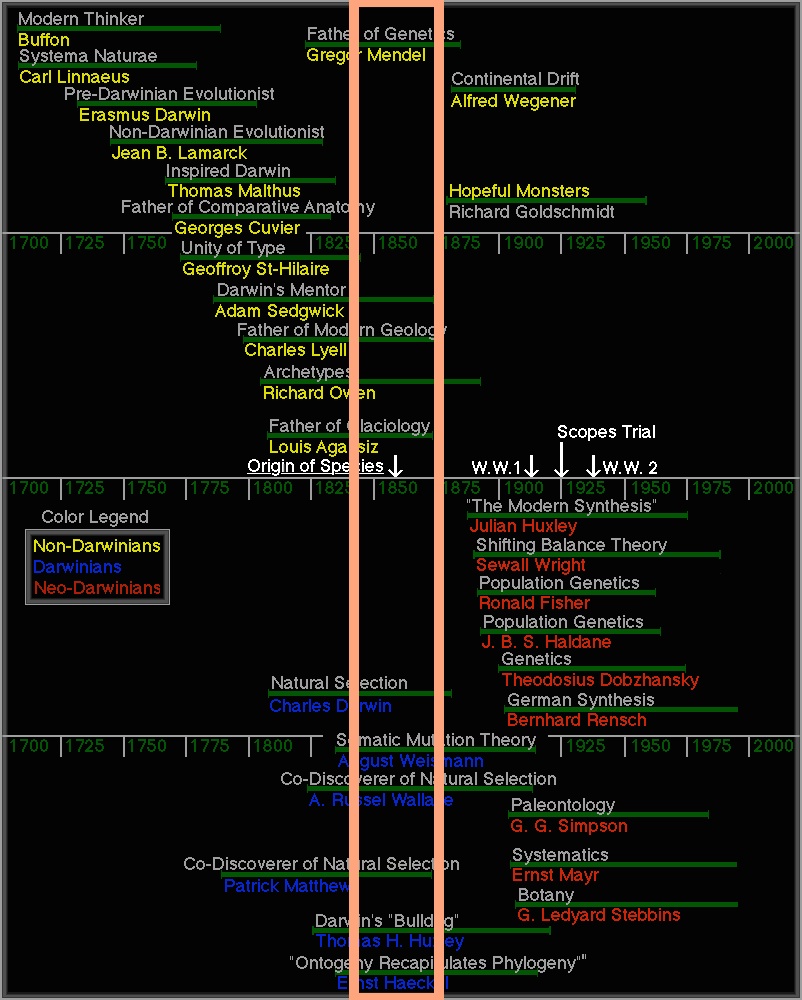

The Mutationism Story in Synthesis tribal mythology

In the mainstream literature of evolutionary biology, history is told in a way that makes things turn out right for the Modern Synthesis, e.g., there is literally an “eclipse of Darwinism”— a period of darkness and strife— that ends when the Modern Synthesis solves the problem of evolution. This self-serving view of history is called “Synthesis Historiography” or SH by professional historians (Amundson, 2005). In SH, critics of neo-Darwinism behave irrationally and hold views with obvious flaws, while Darwin’s followers use reason and evidence to establish important truths.

The stories in SH function as a tribal mythology, i.e., scientists who identify culturally with the “Synthesis” tell these stories to each other to affirm their identity, which is based on a shared belief in their fundamental rightness about evolution, and the wrongness of historic opponents. For instance, in the Mutationism Story, the early geneticists are too stupid to understand populations, gradual change, or selection, which they reject, believing instead that evolution happens by dramatic mutations alone, without selection. The problem is solved when Fisher sees what the mutationists are too foolish to see: there is no conflict between gradualism, selection, and genetics. Versions of this fable are given in this blog (e.g., Dawkins 1987, p. 305 of The Blind Watchmaker; Cronin 1991, p. 47 of The Ant and the Peacock; Ayala and Fitch 1997; Futuyma, 2017; Segerstråle 2002, Oxford Encyclopedia of Evolution 2, pp. 807 to 810; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 2009). Here is Dawkins’s version:

“It is hard for us to comprehend but, in the early years of this century when the phenomenon of mutation was first named, it was regarded not as a necessary part of Darwinian theory but as an alternative theory of evolution! There was a school of geneticists called the mutationists, which included such famous names as Hugo de Vries and William Bateson among the early rediscoverers of Mendel’s principles of heredity, Wilhelm Johannsen the inventor of the word gene, and Thomas Hunt Morgan the father of the chromosome theory of heredity. . . Mendelian genetics was thought of, not as the central plank of Darwinism that it is today, but as antithetical to Darwinism. . . It is extremely hard for the modern mind to respond to this idea with anything but mirth”

Dawkins, 1987, p. 305

Actual history contradicts the Mutationism Story. In reality, immediately upon the discovery of genetics in 1900, early geneticists began to assemble the pieces of a Mendelian view of evolution by mutation, inheritance, and differential survival (Stoltzfus and Cable 2014). The multiple-factor theory was immediately suggested by Bateson and others. Here Bateson and Saunders (1902) give a precise verbal rendition of the Hardy-Weinberg paradigm, the first rigorous paradigm of population thinking:

“It will be of great interest to study the statistics of such a population in nature. If the degree of dominance can be experimentally determined, or the heterozygote recognised, and we can suppose that all forms mate together with equal freedom and fertility, and that there is no natural selection in respect of the allelomorphs, it should be possible to predict the proportions of the several components of the population with some accuracy. Conversely, departures from the calculated result would then throw no little light on the influence of disturbing factors, selection, and the like.”

Bateson and Saunders, 1902, p. 130

Thomas Hunt Morgan won a Nobel prize in genetics. His tendency to refer to “survival” of “definite variations” and to avoid “natural selection” reflects, not a rejection of what we call “selection” today, nor some kind of mental block, but a belief that shifting the goal-posts to avoid accountability is bad for science. For Morgan, the term “natural selection” must be reserved for Darwin’s non-Mendelian theory based on the blending of environmentally stimulated fluctuations (“indefinite variability”), a theory correctly rejected by the scientific community when it was experimentally refuted by Johannsen. Morgan called out the problem of goal-post-shifting when he wrote that “Modern zoologists who claim that the Darwinian theory is sufficiently broad to include the idea of the survival of definite variations seem inclined to forget that Darwin examined this possibility and rejected it.” (Morgan, 1904).

The early geneticists did not reject what we would call “selection” today, e.g., Morgan (1916), in his closing summary, writes that “Evolution has taken place by the incorporation into the race of those mutations that are beneficial to the life and reproduction of the organism” (p. 194). Bateson, Punnett, de Vries and Johannsen were the other early geneticists most well known for their views on evolution. Johannsen and de Vries both carried out successful selection experiments. de Vries begins his major 1905 English treatise by writing that …

“Darwin discovered the great principle which rules the evolution of organisms. It is the principle of natural selection. It is the sifting out of all organisms of minor worth through the struggle for life. It is only a sieve, and not a force of nature” (p. 6)

In Materials for the Study of Variation, Bateson (1894) refers to natural selection as “obviously” a “true cause” (p. 5). Punnett (1905) explains that mutations are heritable while environmental fluctuations are not, concluding that “Evolution takes place through the action of selection on these mutations” (p. 53).

Morgan called out the problem of goal-post-shifting when he wrote that “Modern zoologists who claim that the Darwinian theory is sufficiently broad to include the idea of the survival of definite variations seem inclined to forget that Darwin examined this possibility and rejected it.” (Morgan, 1904).

The views of these influential scientists, and their contributions to evolutionary thinking, were not secrets: they were published, cited and discussed. Bateson, Punnett, Morgan and de Vries all were awarded the Royal Society Darwin medal in the period from 1900 to 1930. That is, the Mutationism Story is not just a wildly distorted version of history: it is a wildly distorted version of history contradicted by sources that are readily accessible to any serious scholar. The ongoing success of this kind of mythology is a testament to the power of propaganda and to the insularity of the Synthesis tribal culture (again, see the conceptual immune system).

Explanatory or methodological mutationism

Explanatory and methodological versions of mutationism are useful to contemplate, by comparison to the flavors of adaptationism identified by Godfrey Smith (2001):

- Empirical adaptationism is ontological, based on a belief about how the world actually is: living things are pervasively adapted, down to the finest detail, and therefore, we will see adaptation everywhere we look because adaptation is in fact everywhere we look, and the explanation for traits will inevitably be functional because traits are in fact inevitably functional.

- Methodological adaptationism holds that, even though adaptation might not be pervasive, it is the thing we are uniquely equipped to study using the methods of science. This view tends to travel together with the ideology that evolution is a combination of selection and “chance”, with the latter being hard to study systematically.

- Explanatory adaptationism is the view that, although selection might not be everything, and although we might be able to study other kinds of causes in evolution, a focus on selection and adaptation is justified because adaptation is the distinctive problem in evolution, and selection is the necessary principle behind adaptation.

Analogously, we can imagine empirical, explanatory, and methodological versions of mutationism. The lucky mutant view mentioned below is one possible ontological or empirical flavor of mutationism. In methodological mutationism, which is clearly a research program in evo-devo, we focus on identifying the mutational-developmental changes involved in evolution on the grounds that this is a distinctively reliable and productive way to study evolution. In explanatory mutationism, our focus is on identifying the detailed mutational-developmental changes underlying changes in form, because explaining changes in form over time is the distinctive challenge of evolutionary biology.

Clearly we can study the evolution of form from a structuralist viewpoint as a series of transformations based on genetic encodings and the intrinsic self-organizing properties of material systems, but we also can study the evolution of form from an adaptationist perspective.

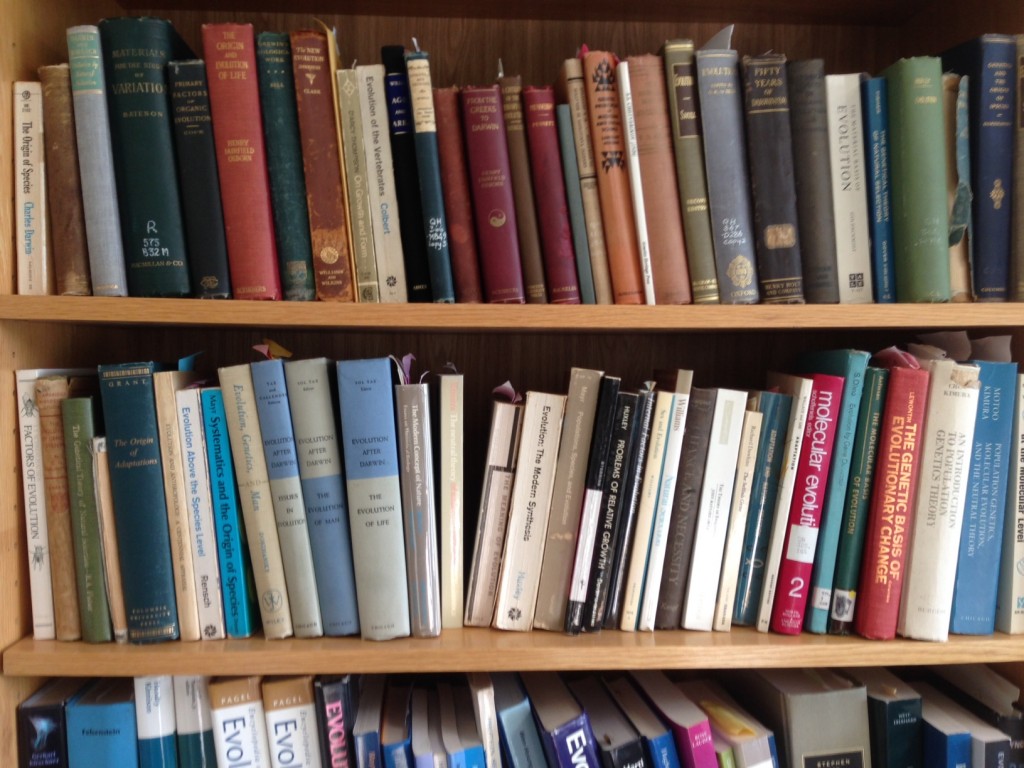

Bateson’s early work exemplifies methodological mutationism: he believed that, in order to understand how evolution happens, the first step was to study variations. Accordingly, his Materials for the Study of Variation is a catalog of 886 numbered cases of discontinuous variations. Bateson planned a second volume on continuous variation but subsequent work on quantitative trait distributions made this unnecessary.

Bateson’s approach was observational, but today we see various experimentally oriented mutationist projects in evolutionary biology:

- attempts to reconstruct mutational changes involved in key changes in development, in the context of evo-devo

- systematic measurements of M in quantitative genetics, e.g., Houle, et al (2017)

- reconstructing ancestral protein molecules and their mutants in order to reconstruct the path of history and test hypotheses (from biochemically-oriented molecular evolutionists, e.g., Dean, Weinreich, Thornton, et al)

- the recent focus on using deep sequencing methods to characterize the mutation spectrum in quantitative detail in a variety of organisms, and in the context of cancer biogenesis

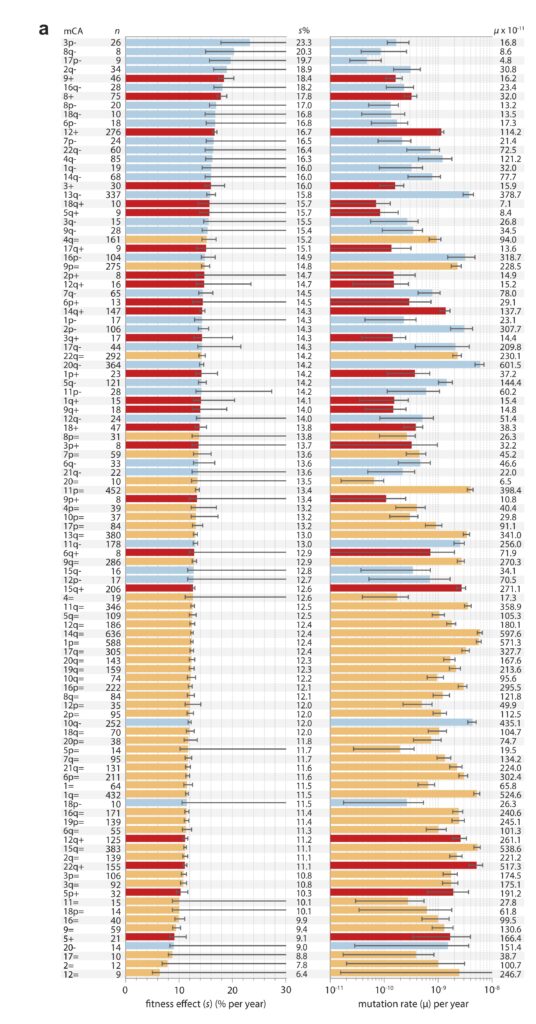

Note that these projects are generally situated in paradigms that are not focused solely on mutation, but also reflect functionalist concerns. This is clearly true of evo-devo, for instance, as the analysis of Novick (2023) makes clear. The evo-devoists are not merely concerned with understanding why certain types of transformations are mutationally and developmentally likely, they are also concerned with selection and function. The same is obviously true of the line of work from Thornton and colleagues, which combines the reconstruction of mutants with functional assays and even selection experiments. In the study of cancer drivers and clonal haematopoesis mutants, contemporary research on mutation spectra, mutation rates, and repair mutants is premised on the understanding that clinical prevalence reflects both the rate of mutational origin and the selection intensity (figure; see Cannataro, et al. 2019; Watson and Blundell, 2022).

If we look at methodological mutationism as an extreme or exclusive position, it is difficult to separate from an extreme form of skepticism about selection that seems unwarranted today, when we can test hypotheses of selection in rigorous ways and assign some non-negligible proportion of the variance in outcomes to selection. Apropos, Nei (2013) does not reject selection as a causal principle in evolution, yet in practice, he seems to reject every attempt to attribute something concrete to positive selection. His approach recalls the attitude of Bateson, who (a century earlier) disparaged adaptationist story-telling by appealing to Voltaire’s Dr. Pangloss, a trope made famous in the “Panglossian paradigm” of Gould and Lewontin (1979). A scientist in Bateson’s time might find it easy to dismiss the vast majority of claims about selection as armchair speculation, not science. Punnett was so deeply skeptical of adaptive explanations that he rejected adaptive mimicry as an explanation for apparently mimetic morphs in butterflies!

Likewise, it’s hard to think of explanatory mutationism as an exclusive position. Clearly we can study the evolution of form from a structuralist viewpoint as a series of transformations based on genetic encodings and the intrinsic self-organizing properties of material systems, but we also can study the evolution of form from an adaptationist perspective.

So, rather than supposing that mutationism is uniquely explanatory for evolution in general, perhaps we can suppose instead that it is distinctively explanatory in some limited but important context. What is the limited but important context in which selective explanations are the least informative or trustworthy, and in which mutational explanations have more power to explain what we wish to understand? I think the best answer here is that there are some aspects of deep divergence, such as the formation of new body plans, major taxa, or key innovations, in which the power of selective explanations is at its lowest—because there are too many degrees of freedom— and the power of mutational explanations are at their highest, e.g., when key innovations can be associated with specific changes in developmental genetics, against a background of conserved features that do not change.

Mendelo-mutationism as a school of thought

The “school of thought” version of Mendelian mutationism is not a unified theory, but a loose collection of beliefs and ideas, overlapping substantially with how the “Modern Synthesis” is construed mistakenly today as a loose collection of beliefs consistent with genetics and selection (see this blog or Stoltzfus and Cable, 2014 for a review).

The early geneticists were the first scientists to accept particulate inheritance and mutation as the foundation of their understanding of evolution, in the sense that they viewed with suspicion any idea that could not be reconciled with particulate inheritance and mutation. Adopting genetics as the foundation for evolutionary reasoning sounds very familiar today, but in 1909 this was a disruptive view that seems to have pissed off evolutionists who were not geneticists, i.e., most of them. Imagine these upstarts telling leading evolutionary thinkers— paleontologists, systematics, embryologists— that the foundation for all thinking in evolution must be particulate inheritance and mutation, new discoveries only understood by a small group of scientists!

As noted above, Bateson and Saunders (1902) clearly articulated the research program of looking for deviations from Hardy-Weinberg expectations as a way of detecting causes other than inheritance.

In the same 1902 paper, they explain what became known as “the multiple factor theory” in which a smooth distribution of trait-values reflects, not blending inheritance and fluctuation, but the joint effect of Mendelian variation at many loci, combined with environmental noise.

Adopting genetics as the foundation for evolutionary reasoning sounds very familiar today, but in 1909 this was a disruptive view that seems to have pissed off evolutionists who were not geneticists, i.e., most of them.

But of course they also considered non-gradual changes via distinctive mutations, i.e., saltations. To the extent that non-gradual changes reflecting distinctive mutations are important in evolution, understanding evolution requires knowing how and when these distinctive mutations arise, based on relevant theories and systematic data. This is why Bateson (1894) catalogued distinctive variations as a way of understanding evolution. Morgan later made a systematic search for mutations in fruit-flies. It was Morgan who first clearly depicted evolution as a series of mutations that are accepted by virtue of being beneficial to the survival of the species. He articulated the concept of a probability of fixation in 1916, distinguishing the case of beneficial, neutral and deleterious mutations (the mathematical problem was later solved partially by Haldane, 1927 and more thoroughly by Kimura, 1962).

Interestingly, it was also Morgan (1909) who first suggested the randomness of mutation as a kind of metaphysical gambit, a working assumption that, so long as the origins of mutations remain a mystery, we will treat them as random and not entertain any ideas in which they have special properties.

Whether definite variations are by chance useful, or whether they are purposeful are the contrasting views of modern speculation. The philosophic zoologist of to-day has made his choice. He has chosen undirected variations as furnishing the materials for natural selection. It gives him a working hypothesis that calls in no unknown agencies; it accords with what he observes in nature; it promises the largest rewards. He does not deny, if he is cautious, the possibility that there may be a purposefulness in the sense that organisms may respond adaptively at times to external conditions; for the very basis of his theory rests on the assumption that such variations do occur. But he is inclined to question the assumption that adaptive variations arise because of their adaptiveness. In his experience he finds little evidence for this belief, and he finds much that is opposed to it. He can foresee that to admit it for that all important group of facts, where adjustments arise through the adaptation of individuals to each other—of host to parasite, of hunter to hunted—will land him in a mire of unverifiable speculation.

Note again the stark contrast between the facts of history and the stories used in Synthesis gatekeeping, in which an association of “mutationism” with directed mutation has been fabricated repeatedly in the attempt to discredit both (Gardner, 2013; Svensson, 2023).

However, Morgan frequently noted that mutations happen at different rates. He and Punnett both believed that this was important for evolution, and might play a role in parallel evolution, citing cases like albino or melanic forms. Under a neo-Darwinian view, melanic forms are expected to emerge gradually, like the all-black rats in Castle’s experiments, from the gradual accumulation of many small differences; and the repeated appearance of melanism in different taxa would indicate that it is some kind of adaptive optimum. For the mutationists, the repeated occurrence of melanic forms suggested that such forms were readily mutationally accessible.

Vavilov (1922) took this idea of parallel evolution by parallel variations to extreme lengths. From his extensive observations of plants, especially crop species, he developed a theory that each major group of organisms has a set of characteristic variants that eventually manifest as distinct species, e.g., if family F has a tendency to produce long-eared forms, this tendency would manifest in genera G1, G2, … each having both long-eared and short-eared species within the genus. He also proposed a kind of mimicry— now called Vavilovian mimicry— that turns out to be quite important among domesticated crop species. In Vavilovian mimicry, the model is a cultivated species actively harvested and propagated by humans, and the mimic starts out as a weed that is eventually propagated by humans by virtue of mimicking the model in terms of the time of maturation, and similar responses to threshing and winnowing techniques. For instance, rye and oats are believed to be Vavilovian mimics that emerged in the context of wheat cultivation (see the wikipedia article on Vavilovian mimicry).

With regard to species and speciation, the early geneticists tended to believe that reproductive incompatibilities were “the true criterion of what constitutes a species” (Punnett, 1911, p. 151). With the Modern Synthesis, this “biological species concept” became the prevailing view (Mallet 2013). They allowed for different kinds of speciation, including speciation by non-Mendelian mutations like de Vriesian macromutations, but also by the accumulation of what we now call “Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller” incompatibilities.

To summarize, the early geneticists opened up and explored a new field, considering a wide range of possibilities (excluding only Lamarckism) and contributing a number of key concepts to evolutionary genetics. Few people know of their accomplishments today because, in Synthesis Historiography, scientific progress only comes from people with the right Darwinian lineage, and not from critics of neo-Darwinism, who are treated as aliens or un-persons. For instance, in Synthesis Historiography, the credit for rejecting 19th-century views of heredity and introducing modern notions of hard inheritance is awarded, not to the geneticists responsible for this innovation, but to 19th-century physiologist and infamous mouse-torturer August Weismann. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Evolution does not have biographic entries for Bateson, de Vries, Punnett, or other early geneticists except for the entry on Morgan, which says nothing of his views of evolution, although he wrote 4 books on the topic. For a graphical example of how the early geneticists are treated as un-persons in Synthesis Historiography, read this.

Lucky mutant (sushi conveyor) dynamics

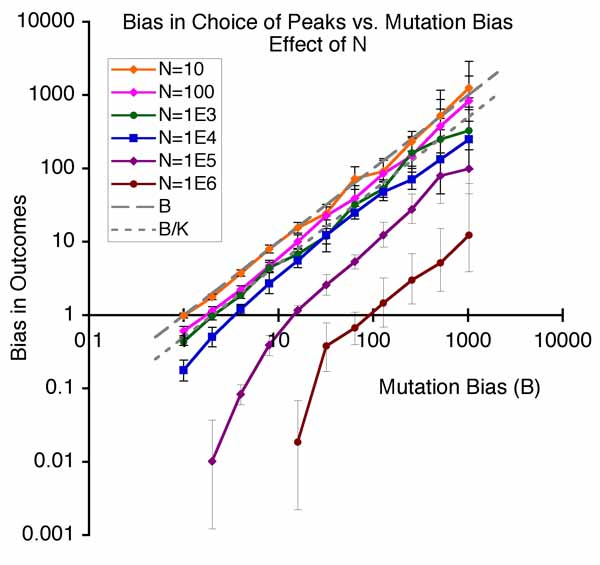

The lucky mutant version of mutationism is a focus on the regime of population genetics in which origination events are important, so that the timing and character of evolutionary change depend on the timing and character of events of mutation that introduce new alleles (or phenotypes). This is sometimes called “mutation-driven” or “mutation-limited” evolution. For me, “mutation-driven” evokes evolution by mutation pressure, so I don’t like the term, but I feel obliged to use it occasionally because this is what some readers recognize. The problem with “mutation-limited” is that, for the vast majority of readers, it suggests some kind of limit to the outcomes that selection can access, whereas for theoreticians this is a statement about dynamics.[3]

As a technical description of dynamics, “mutation-limited” behavior could mean either (1) behavior responsive to changes in u or (2) the limiting behavior as u approaches 0, which is origin-fixation dynamics. When people like Dawkins (2007) invoke the idea that “evolution is not mutation-limited” as a way of discounting a focus on mutation, this only makes sense if it means that evolutionary behavior is not responsive to changes in u, which is what Dobzhansky and others stated explicitly, i.e., they said that changing the rate of mutation would not change the rate of evolution due to the buffering capacity of the gene-pool.

In other words, the most direct label for mutation-responsive dynamics would be “mutation-responsive dynamics” rather than “mutation-limited” or “mutation-driven” dynamics. I have also referred to the “sushi-conveyor” regime of population genetics, as distinct from the “buffet” regime.

Defining “mutationism” as a position on population genetics is not the most historically justifiable way to interpret the views of the early geneticists, because they were not very explicit about population genetics. However, it is how we might choose to see mutationism in retrospective contrast to the neo-Darwinian view of the Modern Synthesis. Darwin’s followers, in their dialectical encounter with the early geneticists, were most concerned to defend the power and creativity of selection, to defend gradualism, and to reject a lucky mutant view of dynamics. They did this by invoking the “buffet” regime of population genetics, in which evolution takes place by shifting the frequencies of alleles present in an abundant gene pool.

Consider again the example of melanic or albino morphs. The repeated occurrence of melanic morphs in related species might suggest to us the possibility of a common mutation to blackness that has occurred repeatedly. Under neo-Darwinism, by contrast, this would only happen by the accumulation of many small effects, i.e., in the same way that all-black rats emerged in the Castle experiment from the accumulation of many small variations. Note that the historic reception of Castle’s experiment illustrated the breadth of mutationist thinking: in a famous dispute with Castle and colleagues, members of Morgan’s group insisted that the gradual emergence of all black and all white rats was entirely consistent with incremental frequency shifts of small-effect alleles under the Mendelian multiple-factor theory, and did not require blending or transformation of hereditary factors, as Castle (under the influence of Darwin’s thinking) had argued.

If “mutationism” means the lucky-mutant view of sushi-conveyor dynamics, then we have seen a broad resurgence of mutationism in evolutionary biology, starting with the molecular evolutionists in the 1960s. See The shift to mutationism is documented in our language.

A transition to …

Finally we can think of mutationism not as a resting point or destination, but as an unstable transition-state on the path to something else. The most productive line of thought, perhaps, is that it points the way toward a paradigm of dual causation that combines functionalism and structuralism, with a major goal of partitioning variance in outcomes to variational and selective causes. A clear and direct recognition of dual causation is evident in statements of Vavilov (1922), e.g.,

“the role of natural selection in this case is quite clear. Man unconsciously, year after year, by his sorting machines, separated varieties of vetches similar to lentils in size and form of seeds, and ripening simultaneously with lentils. The same varieties certainly existed long before selection itself, and the appearance of their series [i.e., combinations], irrespective of any selection, was in accordance with the laws of variation.” (p. 85)

Here Vavilov combines two different kinds of dispositions in one theory, such that each disposition reflects a set of distinct causal processes that are invoked directly in historical explanations. Darwin’s followers would look at the same case and say that variation merely supplies raw material that selection shapes into adaptations, invoking two kinds of causal processes, only one of which is dispositional.

One sees a notion of dual causation expressed very abstractly by Vrba and Eldredge (1984), in their enhanced description of evo-devo thinking:

“Developmental biologists variously stress: (1) how indirect any genetic control is during certain stages of epigenesis; (2) that the system determines by downward causation which genomic constituents are stored in unexpressed form versus those which are expressed in the phenoytpe; (3) that bias in the introduction of phenotypic variation may be more important to directional phenotypic evolution than sorting by selection. This is in contrast to the synthesis, which stresses more or less direct upward causation from random mutations to phenotypic variants, with selection among the latter as the prime determinant of directional evolution.”

Instead of casting evolution as shifting gene frequencies, we can depict it more broadly as a process of the introduction and reproductive sorting of variation in a hierarchy of reproducing entities.[4] To the extent that evolution has any predictable tendencies, they reflect biases in introduction and biases in sorting. This is not simply a re-statement of the position of Vavilov or of Vrba and Eldredge, which is not based on any technical understanding of bias in the introduction of variation as a population-genetic mechanism.

However, the reason for the resurgence of interest in quasi-mutationist thinking— as an attempt to get beyond neo-Darwinism— is that selection does not actually govern evolution in the way that neo-Darwinism supposes. It is a directional factor, but not the directional factor.

The classical functionalist position of neo-Darwinism and the Modern Synthesis focuses on biases in reproductive sorting (i.e., selection) as the cause of everything interesting. The success of this research program is proof that effects of biases in reproductive sorting are profoundly important in evolution. However, the reason for the resurgence of interest in quasi-mutationist thinking— as an attempt to get beyond neo-Darwinism— is that selection does not actually govern evolution in the way that neo-Darwinism supposes. Selection is a directional factor, but not the directional factor. We can also pursue a research program based on the role of generative biases in evolution and, even more broadly, a research program that focuses on both biases in the introduction of variation and biases in the reproduction of variation, with the goal of quantifying their relative influence on the predictability of evolution.

References

Bateson W. 1894. Materials for the Study of Variation, Treated with Especial Regard to Discontinuity in the Origin of Species. London: Macmillan.

Bateson W, Saunders ER. 1902. Experimental Studies in the Physiology of Heredity. In. Reports to the Evolution Committee: Royal Society.

Davenport CB. 1909. Mutation. In. Fifty Years of Darwinism: Modern Aspects of Evolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 160-181.

Dawkins R. 2007. Review: The Edge of Evolution. In. International Herald Tribune. Paris. p. 2.

de Vries H. 1905. Species and Varieties: Their Origin by Mutation. Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Company.

Futuyma DJ. 2017. Evolutionary biology today and the call for an extended synthesis. Interface Focus 7:20160145.

Godfrey-Smith P. 2001. Three Kinds of Adaptationism. In: Orzack SH, Sober E, editors. Adaptationism and Optimality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 335-357.

Gould SJ, Lewontin RC. (classic; CNE theory co-authors). 1979. The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist program. Proc. Royal Soc. London B 205:581-598.

McCabe J. 1912. The Story of Evolution.

Morgan TH. 1904. The Origin of Species through Selection Contrasted with their Origin through the Appearance of Definite Variations. Popular Science Monthly:54-65.

Morgan TH. 1909. For Darwin. Popular Science Monthly 74:367-380.

Morgan TH. 1916. A Critique of the Theory of Evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nei M. 2013. Mutation-Driven Evolution: Oxford University Press.

Novick R. 2023. Structure and Function. In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Poulton EB. 1909. Fifty Years of Darwinism. In. Fifty Years of Darwinism: Modern Aspects of Evolution. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 8-56.

Punnett RC. 1905. Mendelism. London: MacMillan and Bowes.

Punnett RC. 1911. Mendelism: MacMillan.

Segerstråle U. 2002. Neo-Darwinism. In: Pagel M, editor. Encyclopedia of Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 807-810.

Stamhuis IH. 2015. Why the Rediscoverer Ended up on the Sidelines: Hugo De Vries’s Theory of Inheritance and the Mendelian Laws. Science & Education 24:29-49.

Stoltzfus A, Cable K. 2014. Mendelian-Mutationism: The Forgotten Evolutionary Synthesis. J Hist Biol 47:501-546.

Svensson EI. 2023. The structure of evolutionary theory: beyond Neo-Darwinism, Neo-Lamarckism and biased historical narratives about the Modern Synthesis. In: Dickins TE, Dickins JA, editors. Evolutionary biology: contemporary and historical reflections upon core theory. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Vavilov NI. 1922. The Law of Homologous Series in Variation. J. Heredity 12:47-89.

Vrba ES, Eldredge N. (benchmark; co-authors). 1984. Individuals, hierarchies and processes: towards a more complete evolutionary theory. Paleobiology 10:146-171.

Notes

[1] The term “early geneticist” typically means scientists working on mutation and Mendelian inheritance in the first decade of the 20th century (thus Goldschmidt is not considered an early geneticist). The most influential ones were clearly Johannsen, de Vries, Bateson, Punnett, and Morgan. My claim that leading early geneticists did not use the term “mutationism” for their own views is based on published works of Bateson, Punnett, Morgan and de Vries. I’m not going to say they never used it, but I haven’t found a case. I found one instance where Davenport (1909) refers to the view of the “the mutationist”. De Vries literally proposed a MutationsTheorie so it is natural to call him a mutationist. But de Vries’s thinking was extremely complex and mainly non-Mendelian, and the other early geneticists developed their own views, not relying on de Vries’s thinking (for explanation, see Stoltzfus and Cable, 2014).

[2] I’m saying this as an established researcher who is not trying to get a job or tenure, or to curry favor with decision-makers. If you are a junior person, calling out the strawman arguments and shoddy historical scholarship used by influential gatekeepers poses risks to your career, and you should weigh those risks carefully. It’s perfectly all right to leave this fight to others who are not as vulnerable. We all have to pick our battles, and mine are not the same as yours.

[3] For instance, consider evolution under mutation bias on a smooth landscape with one peak. Ultimately the system goes to the peak: mutation places no limits in this sense. However, the rate and trajectory of the approach to the peak will reflect the rate and bias of mutations. So, the dynamics are mutation-responsive but the ultimate outcome and the ultimate level of fitness or adaptation is not limited by mutation. If multiple peaks or destinations are possible, then biases in introduction may be influential. Calling this mutation-limited evolution would just confuse people; saying that it isn’t mutation-limited also would give the wrong impression.

[4] Technically the list should be something more like “introduction, hereditary transmission and reproductive sorting” with biases possible in each process. Biased gene conversion is a transmission bias. So is meiotic drive. Effects of mutational hazard in the thinking of Lynch can be understood as biases in transmission, i.e., longer sequences have lower transmission due to mutational damage (mutational hazard is not an effect of introduction; although it is possible to cast it as a form of selection, that is weird IMHO).