Bad takes #3. Mutation bias as an independent cause of adaptation.

Unfamiliar ideas are often mis-identified and mis-characterized. It takes time for a new idea to be sufficiently familiar that it can be debated meaningfully. We look forward to those more meaningful debates. Until then, fending off bad takes is the order of the day! See the Bad Takes Index.

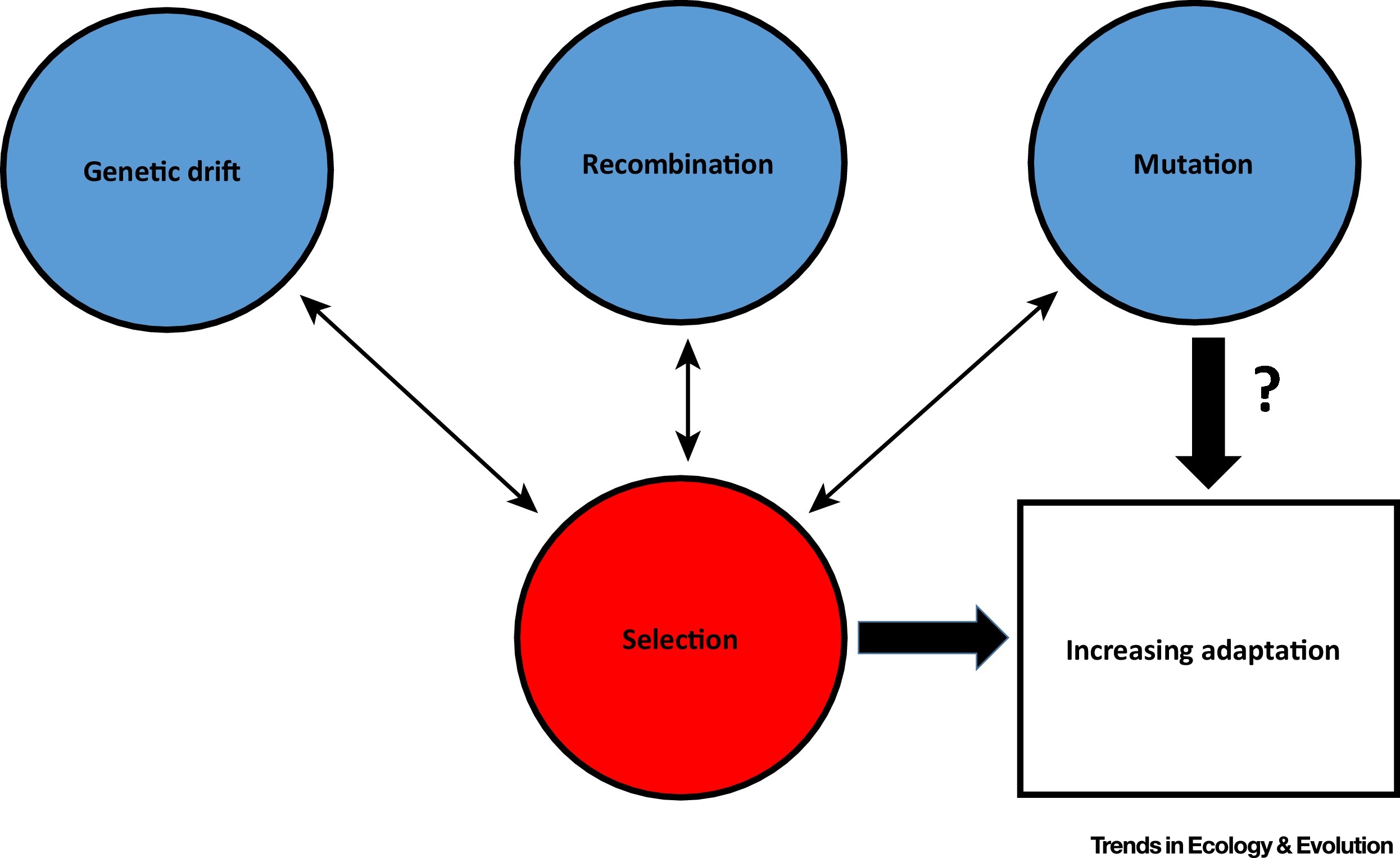

Svensson and Berger (2019) begin their commentary on “The role of mutation bias in adaptive evolution” with a multi-threaded attack on the theory that mutation bias is “adaptive in its own right” or “an independent force” or something that “can explain the origin of adaptations independently of, or in addition to, natural selection.” Just on the first page, they invoke versions of this theory in 5 different places (figure). Clearly, the main purpose of Svensson and Berger (2019) is to debunk this theory of mutation bias as an independent cause of adaptation.

The authors associate this theory with the line of argument on mutation bias and adaptation developed in work from my group (e.g., Yampolsky and Stoltzfus, 2001; Stoltzfus, 2006a, 2006b, 2012, 2019), and extended by studies such as:

- Sackman, et al. 2017. Mutation-Driven Parallel Evolution During Viral Adaptation. Mol Biol Evol.

- Storz, et al. 2019. The role of mutation bias in adaptive molecular evolution: insights from convergent changes in protein function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 374:20180238.

- Gomez, et al. 2020. Mutation bias can shape adaptation in large asexual populations experiencing clonal interference. Proc. R. Soc. B. 287:20201503.

- Cano AV, Payne JL. 2020. Mutation bias interacts with composition bias to influence adaptive evolution. PLOS Computational Biology 16:e1008296.

However, none of these sources promote or assume a theory of mutation bias as an independent cause of adaptation, or a theory of mutation being adaptive in its own right. For instance, in the original twin-peaks model of Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001), the peak favored by the higher selection coefficient is accessible only via a lower mutation rate, and vice versa. Stoltzfus and Norris (2015) worked very hard to establish that— contrary to lore— transitions and transversions that change amino acids hardly differ in their distributions of fitness effects, a result used explicitly by Stoltzfus and McCandlish (2017) as the basis to treat transition bias as something orthogonal to selection.

Clearly, the main purpose of Svensson and Berger (2019) is to debunk this theory of mutation bias as an independent cause of adaptation.

Whereas some other authors have promoted the idea of adaptive mutation (e.g., Cairns, Caporale, Rosenberg), “natural genetic engineering” (Shapiro) or merely some statistical correlations between mutational patterns and fitness effects (Monroe, et al. 2022), the above sources do none of those things.

That is, the theory targeted by Svensson and Berger (2019) is not in the sources listed above, but exemplifies the concept of a strawman argument: misleading readers by presenting a false representation of an alternative view, one that is easy to knock down.

The form of this strawman argument has a long history. Repeatedly, critics of neo-Darwinism have suggested that observed tendencies or directions of evolutionary change are not explained solely by selection, but reflect internal aspects of mutation or development, and advocates of neo-Darwinism have responded by dismissing these ideas as appeals to directed mutation or adaptive mutation, often implying an association with mysticism or teleology (e.g., Simpson, 1967).

Is this simply a case of bad-faith arguments? Perhaps it is— Svensson has refused to correct any of his mis-statements. However, another possibility is that traditionalist thinkers are so strongly indoctrinated that they simply cannot imagine alternative views, or cannot articulate them using judicious language. When internalist critics invoke intrinsically favored directions in phenotype-space, the knee-jerk reaction of traditional thinkers is to treat this as an appeal to intrinsically adaptive directions, because they have absorbed the lesson that the only directions are adaptive ones, and that any other appeal to sources of directions is a kind of witchcraft.

Regardless of the reasons, Darwin’s followers have been misrepresenting internalist claims for a long time, so we know how the advocates of internalist theories tend to respond:

“I take exception here only to the implication that a definite variation tendency must be considered to be teleological because it is not ‘orderless.’ I venture to assert that variation is sometimes orderly and at other times rather disorderly, and that the one is just as free from teleology as the other. In our aversion to the old teleology, so effectually banished from science by Darwin, we should not forget that the world is full of order . . . If a designer sets limits to variation in order to reach a definite end, the direction of events is teleological; but if organization and the laws of development exclude some lines of variation and favor others, there is certainly nothing supernatural in this” (Whitman, 1919: see p. 385 of Gould, 2002)

Here Whitman is literally explaining that orderly tendencies may arise from strictly physical processes with no requirement for supernatural influences. But for Simpson (1967), this kind of idea refers to “the vagueness of inherent tendencies, vital urges, or cosmic goals, without known mechanism.”

In general, when deceptive arguments against alternative views are maintained and nurtured for generations, this is because they are being used, not to resolve substantive scientific questions, but to maintain conformity within a closed ideological system, i.e., advocates of neo-Darwinism use these arguments to reinforce their prior beliefs and shut out new ideas that might alienate them from colleagues or create cognitive dissonance. Gatekeepers like Svensson and Berger discourage new thinking by presenting it as bad science or sensationalism, relying on the same fatuous strawman used in a century of prior gate-keeping.

Of course, we must not confuse theories and people, e.g., a theory supported by legions of trolls making bad arguments does not become a bad theory for this reason. The theory and its apologetics are two different things. We can define neo-Darwinism clearly in terms of the dichotomy of the potter (selection) and the clay (variation), and this concept stands by itself. Separate from this, there is a culture or a set of rhetorical practices associated with neo-Darwinian apologetics. It is this neo-Darwinian culture or thought-collective that has a sociological aspect and a self-protective urge that gives rise to the same kinds of pathologies as any cult or identity-group.

The false accusations of teleology or directed mutation are part of the conceptual immune system of the neo-Darwinian thought-collective (described in a separate post). The system is based on excluded middle arguments in which alternatives like saltationism, orthogenesis, and mutationism are presented only as crazy extremes. The system is used in two ways. The first line of defense is to present alternative views as being inherently flawed or absurd: they represent mental errors that can be dismissed a priori, without any difficult research or analysis. In the version of history that neo-Darwinians teach, critics of neo-Darwinism behave irrationally and hold views with obvious flaws (see Stoltzfus, 2017).

Eventually, however, some of the more intellectually rigorous thinkers begin to sense that scientific theories are supposed to stand for something substantive and risky, and they begin to consider the plausibility of alternatives to neo-Darwinism. In this case, the guarantors of tradition must offer a more sophisticated argument. In this second line of defense, the previously excluded middle is transformed, minimized, and appropriated for tradition. That is, the alternative is granted as a theoretical possibility, but its importance is minimized, it is presented in a modest or disguised form using different language, and it is grounded in a tradition that is associated with neo-Darwinism, by reference to obscure passages in the sacred texts. The defense shifts from a specific falsifiable theory to a flexible tradition or thought-collective. The thought-collective is defended by using ambiguity to shift the focus of discussion away from radical thoughts, and toward vague suggestions emanating from the pantheon of heroes.[1]

Svensson and Berger (2019) illustrate both strategies. First they attack the straw-man of “independent cause of adaptation,” then they present a more reasonable idea based on population genetics— a butchered version of the theory proposed by Yampolsky and Stoltzfus (2001)—, and present this as conventional wisdom (although practically unimportant). They do this in multiple ways. First they state that the theory is part of the neutral theory— which in their curious conception of history was somehow swallowed up post hoc by the Modern Synthesis— but they cite no source for this, e.g., if Kimura actually said this in his 1983 book or his hundreds of papers, they could have cited Kimura, but they don’t. Then they imply that Dobzhansky understood the theory, citing a vague and indirect comment about similarities of “germ plasm” (in a pre-Synthesis source that refers explicitly to Vavilov’s mutationist theory of parallelism!). Then they present a derivation of a key equation for effects of arrival bias in Box 1. This box gives a short series of mathematical results and names Haldane, Kimura, and Fisher without naming Yampolsky and Stoltzfus, subtly guiding the reader to assign the credit to famous dead people rather than to the living authors who actually proposed the theory and derived the equation.

However, at the same time that they appropriate the theory on behalf of Fisher, Dobzhansky, Kimura and others, they also purport to undermine it by dismissing the empirical evidence and claiming that the theory depends on unusual conditions including sign epistasis and drift in small populations, even though the model they depict in Box 1 has no clear dependence on either of these conditions (indeed, these are not actual requirements, but fabrications debunked by Couce, et al).

For more bad takes on this topic

This is part of a series of posts focusing on bad takes on the topic of biases in the introduction of variation, covering both the theory and the evidence. For more bad takes, see the index to bad takes.

References

Gould SJ. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Simpson GG. 1967. The Meaning of Evolution. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. The quoted passage appears on p. 159.

[1] This passage really needs more concrete examples but I’ve written about this elsewhere. Futuyma’s Synthesis apologetics are a rich source of appropriation arguments (for examples, see this blog), e.g., Mayr is called on to appropriate developmental bias as part of the Synthesis, and Fisher, of all people, is called on to appropriate saltations.