Bad takes #1. We have long known

Unfamiliar ideas are often mis-identified and mis-characterized. It takes time for a new idea to be sufficiently familiar that it can be debated meaningfully. We look forward to those more meaningful debates. Until then, fending off bad takes is the order of the day! See the Bad Takes Index.

A reviewer of Stoltzfus and Yampolsky (2009) wrote that “we have long known that mutation is important in evolution,” citing the following passage from Haldane (1932) as if to suggest that the message of our paper (emphasizing the dispositional role of mutation) was old news:

A selector of sufficient knowledge and power might perhaps obtain from the genes at present available in the human species a race combining an average intellect equal to that of Shakespeare with the stature of Carnera. But he could not produce a race of angels. For the moral character or for the wings, he would have to await or produce suitable mutations

We included this in the final version of the paper because, actually, this passage demonstrates the opposite of what the reviewer implies. What is Haldane suggesting?

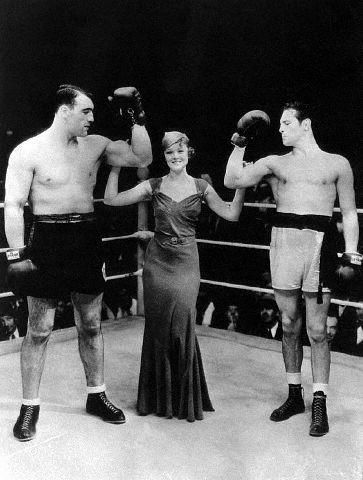

I can’t resist a good story, so let’s begin with this 1930s photo of Italian boxer Primo Carnera, his friend and fellow heavyweight champ Max Baer, and Hollywood actress Myrna Loy. Baer dated Loy in real life. They made a movie together, the three of them (thus the staged publicity photo). Baer, one of the greatest punchers of all time and half-Jewish, became a hero to a generation of Jewish sports fans when he demolished Max Schmeling, the German champion, prompting Hitler to outlaw boxing with Jews. He literally killed one of his opponents, and repeatedly sent Carnera to the floor during their single fight.

But the point of this picture is that, although Baer was a formidable man, Carnera makes him look small. Other fighters were afraid to get in the ring with him. Though enormous — 30 cm taller and 50 kg heavy than the average Italian of his generation —, Carnera was not the aberrant product of a hormonal imbalance. This photo shows a huge man who is stocky but well proportioned, muscular, and surprisingly lean. Again, he was not a misshapen monster, but a man at the far extremes of a healthy human physique, which is precisely Haldane’s point.

Selective breeding to the quantitative extremes of known human ability, Haldane proposes, could produce a race combining the extreme of Carnera’s stature with Shakespeare’s magnificent verbal ability.

Haldane contrasts this with a different mode of evolution dependent on new mutations, which might produce a race of pure-hearted, winged angels, if one could wait long enough for the mutations to happen. That is, Haldane is contrasting (1) a mode of evolution that is gradual and combinatorial, bringing together known extremes, with (2) a mode of evolution that could generate imaginary fictitious not-real creatures. Haldane, Wright and Fisher each argued that a mode of change dependent on new mutations would be too slow to account for the observed facts of evolution. They argued instead that evolution must take place on the basis of abundant standing variation, a former orthodoxy that is largely forgotten today.

That is, in the passage above, Haldane is not endorsing a mode of mutation-dependent evolution, but gently mocking it, in contrast to a mode of evolution that, based on quantitative standing variation, could produce a race of magnificently eloquent champions.

Thus, the reviewer has missed Haldane’s meaning.

To understand what this reviewer is trying to accomplish via this “we have long known” argument, let’s imagine an alternative universe in which the reviewer says this:

“We have long known about the important role of biases in the introduction process emphasized in this manuscript. Haldane (1932) and Fisher (1930) explored the theoretical implications of such biases (under regimes of origin-fixation and clonal interference); Simpson and many others incorporated a theory of internal variational trends (i.e., orthogenesis) into their interpretations of the fossil record. Therefore, the authors’ implicit claim of novelty is unfounded. The theory is simply not new and not theirs, and they need to cite the proper sources for it.”

Of course, the reviewer does not say this, because nothing like this ever happened. In our universe, Fisher and Haldane failed to explore this theory (origin-fixation models didn’t appear until 1969, and clonal interference was not formally modeled until much later). In our universe, Simpson and others mocked the idea of orthogenesis.

Certainly, the reviewer is correct that scientists in the mainstream Modern Synthesis tradition have always known that mutation is important in evolution. Haldane, Fisher, Ford, Huxley, Dobzhansky, and others said explicitly that mutation is ultimately necessary, because without mutations, evolution would eventually grind to a halt.

However, they did not say that mutation is important as a dispositional factor. Instead, they argued explicitly against this idea, e.g., Haldane (1927) is the original source of the argument that mutation pressure is a weak force (see Bad takes #2).

The theory of biases in the introduction process, by contrast, says that mutation is important in evolution as a dispositional cause, a cause that makes some outcomes more likely than others, and that this importance is achieved (mechanistically) by way of biases in the introduction process.

So, the reviewer is doing a rhetorical feint (aka bait-and-switch argument): the words “we have long known…” encourage the reader to think that he is going to undermine the novelty of the theory, but his actual claim fails to do this. The theory of biases in the introduction of variation is a specific theory, linking certain kinds of inputs with certain kinds of outputs, via a certain kind of population-genetic mechanism. And the reviewer is responding to this theory by saying “we have long known that mutation is important” which is not the same thing. The words “mutation is important” do not by themselves specify this theory— or any theory—, and in fact, the traditional importance assigned to mutation is clearly not “dispositional cause that makes some outcomes more likely than others” but “ultimate source of raw materials without which evolution would grind to a halt.” These are two utterly different theories about the role of variation, and only one of them is traditional and neo-Darwinian.

Finally, it is important to understand the role of flimsy “we have long known” arguments in evolutionary discourse. The pattern of the argument is that it appears to undermine a claim of novelty by identifying the same claim in traditional sources, but what is actually happening is that a specific target is being swapped out for something else, often a fuzzy or generic claim. The novelty of X is rejected on the grounds that X sounds a lot like old theory Y, or because both X and Y can be categorized as a member of some larger and fuzzier class of claims, e.g., “chance” or “contingency” (see Bad Takes #5: Contingency). This is often the case with “we have long known” arguments emanating from traditionalist pundits.

Again, if a theory X is actually unoriginal, pundits don’t need to make vague “we have long known” arguments, but can simply cite the original source of X per standard scientific practice. It is precisely when X is new that traditionalist pundits must construct vague “we have long known” arguments to rescue tradition from its failures.

References

Haldane JBS. 1932. The Causes of Evolution. New York: Longmans, Green and Co.

Stoltzfus A, Yampolsky LY. 2009. Climbing mount probable: mutation as a cause of nonrandomness in evolution. J Hered 100:637-647.